American disenchantment with the government after the end of the Vietnam War in the late 1960s through 1970s has since grown to be also disenchanted with the American dream. The September 11th terrorist attacks in 2001 is the primary marker for the radical change in American sentiment and the defining moment of the so-called “millennial generation,” the generation of people who were in primary school through college during the attacks. As Americans struggle to make sense of the War on Terror, their sentiment toward the government was often conflicted, confused, and frequently changed. Though the war began with a patriotic fervor inspired by the Bush administration, a sentiment of indifference emerged a few years into the war with the exception of a few major bloody events. Dissention characterized the later years until President Obama declared in 2013 that the United States to no longer be pursuing the War on Terror. Between the indifference and dissention stages, the American dream changed and even became irrelevant.

In the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, more superhero films were being produced than in any other period in American history. Historians can use the numerous superhero films just as Americans used them when they were release since these films provide explanations of the War on Terror for Americans to make sense of it and reflect how Americans perceived the war at the time.[1] The “good guys” in popular culture realms tended to be either superheroes acting outside of the federal government, as is the case in the numerous Marvel films produced since 2001, or common Americans who sometimes take extralegal actions, disregarding the government though they work for it. In the latter case, examples from Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker (2008) and the current television show Homeland depict American soldiers and intelligence agents disregarding official orders to stop pursuing a case so they can essentially be the heroes and save the world without government help. In Homeland’s first season, CIA agent Carrie Mathison carries out an investigation against executive orders, which ultimately turned out to be the right thing for her to do to protect important government officials.

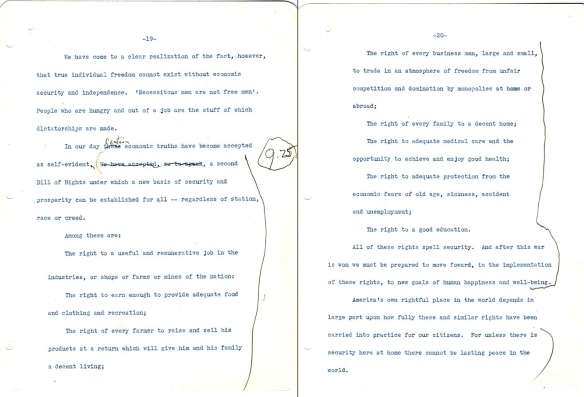

In Homeland season 1, Carrie has a wall of classified documents (stolen from Langley) in her house for her unsanctioned investigation

Similarly in The Hurt Locker, Sergeant James refuses to follow orders, but his disobedience ultimately saves the lives of hundreds of people. In these films, the federal government is often portrayed as a hindrance, something likely to cause more harm than good, particularly in Homeland. Eventually, vigilante soldiers and superheroes became the ideal American hero for much of American society during the War on Terror.

While Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker provides intense scenes of battle and the everyday lives of soldiers in Iraq during the War on Terror to actively show the affects of war on soldiers, no war or intense action is seen in Ben Fountain’s novel Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk. Instead of filling the novel with the heroic actions of the story’s soldier hero, Fountain focuses on how Billy interprets his life and American life through a stream of consciousness narrative. Billy’s thoughts throughout the book, like The Hurt Locker, show how being on the battlefield affects young people, but his interactions with non-military characters in the book show how the War on Terror has affected Americans at home. The War on Terror simultaneously made sense and made no sense at all for many Americans in the early twenty-first century. The fact that films attacking the idea of the War on Terror were hardly successful early in the war suggests that Americans initially wanted to support the war effort. It seems that nearly every American knew someone, friend or family, who served in the war and believed he or she had to support the war effort to support their friend or family member, regardless of their moral leaning toward the war. Being conflicted over supporting the troops or opposing a war they most often did not understand created indifference and dispiritedness among Americans.

The fact that the Fountain’s story does not have an end goal to lead up to really pushes the point of the novel through Billy’s eyes, that there is no clear purpose to life. The morality of the war is not in question in Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk or in The Hurt Locker, but rather their individual purpose in life and the purpose of the United States. Billy points out the United States’ complicity in the war and that Americans are instead “stuck on teenage drama, on extravagant theatrics of ravaged innocence and soothing mud wallows of self-justifying pity.” His experience during his two week “victory tour” in the United States shows him the American life for which he is fighting. Billy is not impressed by the “draft-dodging, platitude-mouthing millionaires and their trophy wives…[or] a scantily clad Beyoncé entertaining football fans with a ridiculous military-themed halftime show.” For Billy Lynn in Fountain’s novel and Sergeant James in Bigelow’s film, being separated from the trivial aspects of American life, they realize that the war has made them foreigners in their home country and decide their life’s purpose is war. War had become a way of life in the early twenty-first century.

War being a way of life is not the point of the novel or the film. Both use the “war as a way of life” mentality to capitalize on the excessiveness of American culture. When James has returned to the States from Iraq at the end of the film, he is very clearly overwhelmed by the excessive number of food choices when his wife asks him to buy cereal. Similarly, Lynn finds the expensive leather and crystal Cowboys’ merchandise at the Texas Stadium absurd and jokes with Mango about it.[2] The American dream of being economically comfortable, married to a beautiful woman, and having a house filled with happy children is lost on both these soldiers and American society in general. Billy sees distorted images of the old American dream among the wealthiest crowd at the Cowboys’ game. James actually has achieved the old American dream, but returning to it from war makes his life seem empty and purposeless.

Similarly, Lynn finds the expensive leather and crystal Cowboys’ merchandise at the Texas Stadium absurd and jokes with Mango about it.[2] The American dream of being economically comfortable, married to a beautiful woman, and having a house filled with happy children is lost on both these soldiers and American society in general. Billy sees distorted images of the old American dream among the wealthiest crowd at the Cowboys’ game. James actually has achieved the old American dream, but returning to it from war makes his life seem empty and purposeless.

Billy’s interpretation of civilian life during the War on Terror thoroughly describes Americans conflicted emotions toward the war. His encounters show people who seem to have forgotten or simply do not care enough about the war until in the soldiers’ presence as well as people openly opposed to the solders’ line of duty.[3] Sergeant James’ story embodies the heroic vigilante soldier Americans favored at the time, a reflection of American sentiment toward their government. Both Billy and James reflect indifference to the traditional American dream and the adoption of a war way of life without regard to their moral judgment concerning the war.

__________________________________________________________________________

[1] Drew McKevitt, “Watching War Made Us Immune: The Popular Culture of the Wars,” in Understand the U.S. Wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, eds. Beth Bailey and Richard H. Immerman (New York: NYU Press, 2015), 4.

[2] Ben Fountain, Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 2012), 29.

[3] Ben Fountain, Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, 301-307.